Seven Delicious Twists on the Humble Hummus Recipe

To continue our celebration of #MedMonth and to honour International Hummus Day, we’ve collected 7 delicious hummus recipes to get your taste buds excited. What easier way to enjoy these nutritious pulses than whizzing them up into a creamy dip in a blender?

The meal possibilities for hummus are endless. It can be served as a dip, spread or with salad. Any of the recipes here (except the sweet hummus) are a great addition to a Budda bowl. For a snack or light lunch, serve any of the hummus recipes with toasted wholewheat pita bread slices and raw sliced veggies for dipping.

Get your can of chickpeas ready and choose your favourite variation to try out first. Snap a photo and tag us on social to let us know what your favourite hummus recipe is. We’re on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Before we dig into the recipes, here are a couple of general tips for perfect hummus every time:

Pour in the olive oil during processing until the ideal consistency is reached.

Add a dash of cold water to help make it smooth and creamy.

For extra smooth hummus, remove the skins by gently rolling the chickpeas in a clean kitchen towel before using.

Don’t discard the aquafaba (the chickpea water)! If your hummus is too thick, add some instead of water when processing. Or, use it in another recipe – aquafaba is great as an egg replacement in desserts such as dairy-free mousse.

Using animals to convert plant protein to animal protein in meat and dairy products is inefficient. Eggs have the highest protein conversion efficiency, meaning 25% of the protein in animal feed is efficiently converted to protein in the animal product (2). The remaining 75% of protein is lost conversion. Poultry, pork, and red meat are less efficient with protein conversion efficiencies of roughly 20, 8.5, and 4% respectively (2). With this inefficient conversion other health promoting components of plant proteins are also lost, such as fiber, and instead animal proteins are packaged with saturated fat which have negative health effects.

Those who eat animal products are most likely also consuming soy, albeit indirectly. For example, 1 kg of chicken requires more than 600 grams of soy chicken feed. Furthemore, the average Dutch person eats about 23 kg of chicken per year, which translates to an indirect yearly intake of more than 13 kg of soy chicken feed (yum!) (3). If you also add the average consumption of soy from pigs and beef, you arrive at a total of more than 30 kg of soy that ends up on the plate of the average omnivore indirectly via the feed of chickens, pigs, and cows. And let us not forget the soy that’s required to feed the cows producing milk, yoghurt, and cheese, or the chickens laying eggs.

Image: Hidden soy: amount of soy feed required for animal products. Adapted from the Soy Barometer 2014 (4)

In comparison, it is estimated that the average Western vegan consumes about 10-12 grams of soy protein per day, which is approximately 350 ml of soy milk (5). If we translate this back to ‘animal feed’, this compares to eating 11 kg per year. An average omnivore consumes about 3 times as much soy as the average vegan via meat.

Soy production and its environmental impact

Nearly 70% of all soy used today comes from the US or Brazil (6). Over the last 60 years, the demand for soy has increased dramatically. Most of this growth has come from increased demand for processed soy for animal feed (70% of global demand), biofuels and vegetable oil. By 2013, the demand for processed soy increased from 88 million to 227 million tons. Yet, during this period, demand for soy products such as tofu and soy milk increased by only 3 million tons (6). This is no surprise. Global meat production has more than tripled over the past 50 years. This increase is strongest in poultry – the largest consumer of soy feed.

Although the area used to grow soy has more than quadrupled, several studies come to a similar conclusion: the direct causes of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest are largely due to grasslands for cattle ranching, not soy production (7-9). Yet, soy still plays a significant role when we take its indirect impacts into account. Because most deforestation is driven by expanding pastures for beef, or soy to feed poultry and pigs, for consumers reducing meat consumption is a key way to make an impact (6).

Kid with Raspberries

Genetically modified soy

More than half of the world’s soybean production is genetically modified. Assuming 30 kg of animal feed is needed per year per person for meat production, it is likely that the average omnivorous Dutch person indirectly ingests about 15 kg of genetically modified soy via meat and poultry.

Most soy products made for human consumption, for example from brands such as Alpro, are not made from genetically modified soy (10). Any product containing genetically modified soy must state it clearly on its packaging. European legislation requires that if a product contains more than 0.9% genetically modified ingredients, it must be stated very clearly on the packaging (11). This rule does not apply to animal products derived from animals that have eaten genetically modified feed. In organic livestock farming, animals are not fed genetically modified soy. So, if you wish to eat meat, drink a glass of milk, or scramble an egg from animals that have not been fed genetically modified food, choose organic. If you don’t care, you will most likely be ingesting food produced using genetically modified soy. Whether or not genetically modified soy is bad for your health is not discussed here. The reality is: we don’t know.

Soy and breast cancer

Soy contains phytoestrogens. These are plant substances (phyto) that are similar to female hormones (estrogens) in the body. This is the reason why some people think soy increases the risk of breast cancer or causes so-called “man boobs”!

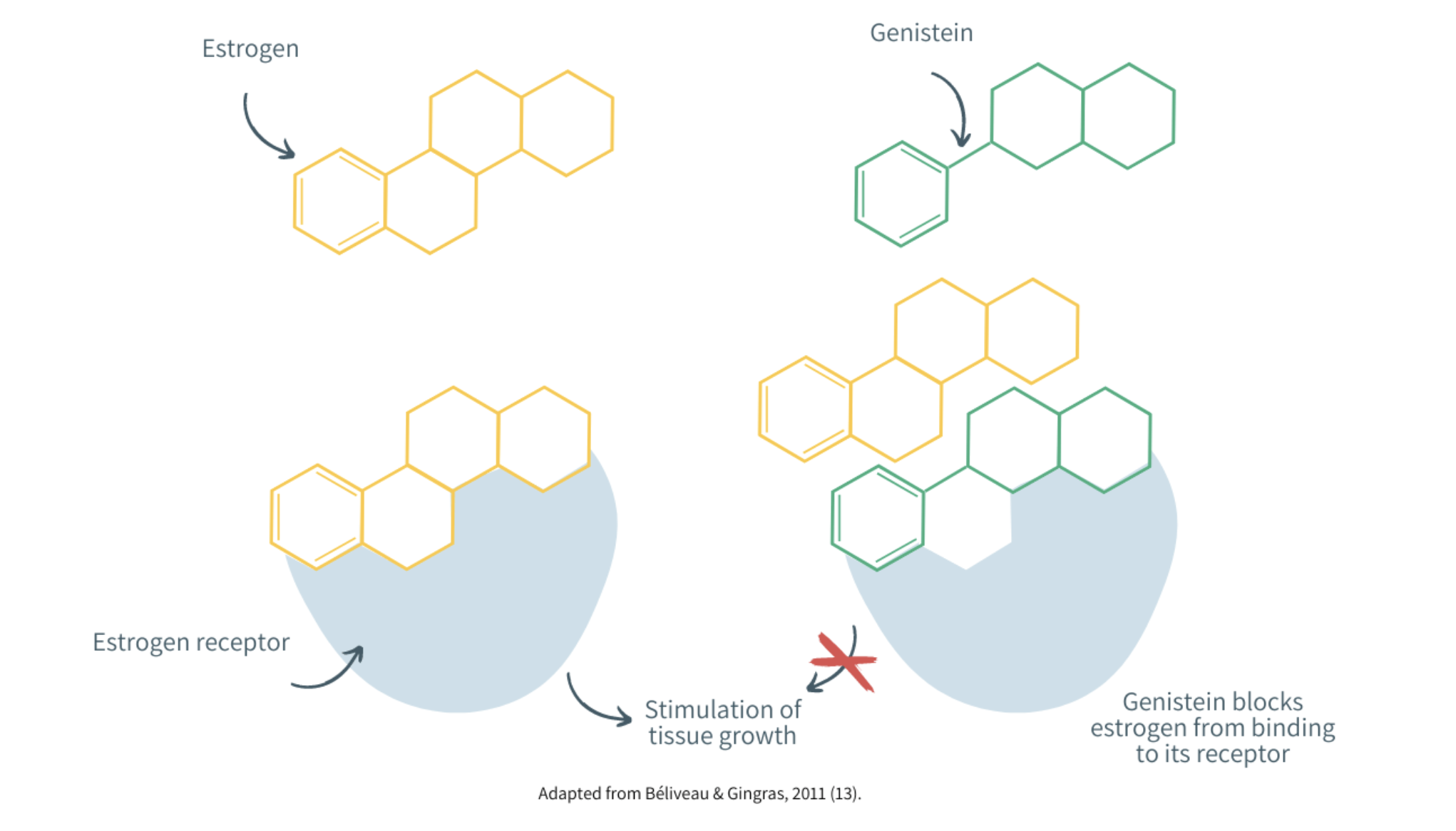

However, recent research shows that soy consumption does not increase the risk of breast cancer, and instead may decrease it (12). In the figure below you can see why this may be the case, explained using genistein, a phytoestrogen found in soy. Because estrogen and phytoestrogens look alike, phytoestrogens can attach to the body’s estrogen receptors. But, instead of activating these receptors (and thus stimulating tissue growth), in some cases, they occupy them and block the real estrogen from being able to bind (thus reducing the stimulation of tissue growth) (13).

Studies evaluating the effects of soy and phytoestrogens on breast cancer tumor incidence and growth in mice and rat models have shown variable results (14). Yet, it has become apparent that mice and rats metabolize phytoestrogens differently than humans and thus the translation of these studies to humans should be done with caution (15,16). Although more research needs to be done, recent studies conclude that soy is likely to have a protective effect against cancer in general, especially lung and prostate cancer (17). The possible protective effects of soy are based on studies with soy-containing foods, not soy supplements.

It is also interesting to look at the difference in breast cancer cases between Europe and Asia. Countries with the highest number of breast cancer cases, yet relatively low soy consumption, include Belgium, Denmark, France, and the Netherlands (18). In these countries, 315-335 out of 100,000 people (age-standardized) develop breast cancer yearly. Contrarily, in countries like Japan, China, Thailand, and Indonesia, known for relatively high soy consumption, breast cancer cases remain between 140 and 280 per 100,000 people (19). Although this may also be due to other factors, various review studies conclude that soy appears to have a protective effect against breast cancer, especially in women who have had breast cancer before (20, 21). On the other hand, dairy from cows has been linked to a higher risk of death from breast cancer and a higher risk of prostate cancer in men (22, 23). Also, red meat has also been associated with an increased risk of cancer in general and in particular breast cancer (24).

Should we be worried about phytic acids?

Phytic acids are mainly found in nuts, grains, and legumes, including soy. Phytic acids are said to hinder the absorption of minerals such as zinc, iron, and calcium as they can bind to minerals in our body and are then excreted through the intestines. As a result, some may refer to them as anti-nutrients and therefore vegans who consume a relatively large amount of phytic acids could theoretically suffer significant deficiencies. However, this does not appear to be the case (25).

Studies show that consuming too many phytic acids in a deficient diet (think of developing countries or one-sided diets) can indeed aggravate the situation. Yet, this does not appear to be the case in those eating a well-balanced diet. Given the diseases that we frequently see in Western countries, it is much more interesting to look at the benefits of phytic acids. For example, phytic acids appear to be an antioxidant and have protective effects against cancer and atherosclerosis (26). Also, fermented soy products such as tempeh, miso, and soy yoghurt contain fewer phytic acids than non-fermented products, such as tofu, because they are broken down during the fermentation process.

Soy and thyroid health

Research and experience show that soy can have some impact on the thyroid gland (27, 28). Although research shows that soy does not cause a slow thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), soy can impair the absorption of iodine, and iodine is needed to make thyroid hormones. It is therefore important to ensure that the intake of iodine is also sufficient. Iodine can be found in iodized salt and bread, or seaweed. In general, if you use thyroid medicine, it is good to consult a doctor or dietician, because soy (supplements) and fibre-rich foods can reduce the absorption of these medicines (29).

Other health benefits of soy

Inflammation or chronic, low-grade inflammation in the body is a root cause of many diseases of affluence. Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer are associated with inflammation. Soy consumption appears to protect against inflammation, lowers LDL (‘bad’ cholesterol), reduces hot flashes, promotes glucose metabolism, relieves depressive symptoms and improves skin health (30-32). To unlock the LDL-lowering potential of soy, aim for an intake of 25 g soy protein per day as its effects have been shown at this level (31).

CLASSIC HUMMUS

Ingredients

400 g cooked chickpeas, drained (set aside a few whole chickpeas for the decoration)

6 cloves of garlic

juice of 2 lemons

8 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

4 tbsp tahini

1 tsp ground cumin

salt & pepper (to taste)

Preparation

Add all ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Transfer to a bowl and top with the whole chickpeas and a dash of olive oil. Optionally, sprinkle with fresh chopped parsley and sweet or smoked paprika.

Serve with toasted wholewheat pita bread slices and raw sliced veggies for dipping.

BEETROOT HUMMUS

Ingredients

250 g cooked beetroot

400 g cooked chickpeas, drained

2 cloves of garlic

juice of 1 lemon

3 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

2 tbsp tahini

1⁄2 tsp ground cumin

salt & pepper (to taste)

Preparation

Chop the beetroot into bite-size pieces.

Add all ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Serve as a spread on whole wheat or sourdough bread rolls.

SUN-DRIED TOMATO HUMMUS

Ingredients

800 g cooked chickpeas, drained

10 sun-dried tomatoes

2 tbsp oil (from sun-dried tomato jar)

juice of 2 lemons

2 cloves of garlic

2 tbsp tahini

1 tsp dried oregano

1⁄2 tsp sea salt

50 g pine nuts

Preparation

Lightly toast the pine nuts in a dry pan (no oil) and set aside.

Add all other ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Serve with the toasted pine nuts on top, and drizzle with extra virgin olive oil.

GINGER & TURMERIC HUMMUS

Ingredients

400 g cooked chickpeas, drained

3 cm of ginger, peeled and grated

1 clove of garlic

juice of 1 lemon

2 tbsp tahini

2 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

1 tsp turmeric powder

salt & pepper (to taste)

Preparation

Add all ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Drizzle with olive oil and sprinkle with fresh chopped parsley.

Serve with the veggie dipping sticks of your choice!

ROASTED SWEET POTATO HUMMUS

Ingredients

1 small / medium sweet potato

1 tsp extra virgin olive oil

400 g cooked chickpeas, drained

1 clove of garlic

2 tbsp tahini

2 tbsp of lemon juice

salt & pepper (to taste)

1 tsp cinnamon or pumpkin pie spice

Optional: a dash of maple syrup to sweeten

Preparation

Preheat oven to 200°C. Cut the potato into cubes and toss in oil.

Roast for 15 – 20 minutes until cooked. Set aside and allow to cool.

Add potato and remaining ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

GREEN LENTIL HUMMUS WITH HERBS AND OLIVES

Ingredients

250 g green lentils, cooked and drained

70 g kalamata olives, pitted

juice of 2 lemons

2 cloves garlic

4 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

2 tbsp tahini

1⁄2 tsp cumin

2 tbsp sunflower seeds

fresh, chopped parsley

Preparation

Lightly toast the sunflower seeds in a dry pan (no oil) and set aside.

Add all ingredients (except sunflower seeds and parsley) into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Transfer to a bowl and sprinkle with the sunflower seeds and parsley.

SNICKERDOODLE HUMMUS (SWEET)

Ingredients

400 g cooked chickpeas, drained

2 tbsp almond butter

2 tbsp date syrup

2 large dates

3 tbsp unsweetened plant milk

2 ½ tsp vanilla extract

1 ½ tsp cinnamon

pinch of salt

Preparation

Add all ingredients into a food processor and blend for about 2-3 minutes, until nice and smooth.

Allow hummus to chill in the fridge for a couple of hours before serving. Resist the temptation to eat it straight out of the blender!

Serve with fresh fruit such as apple slices, bananas and berries, or spread on rice crackers or whole wheat toast.

-

Carlijn Wagenaar, MD is the Chairperson for the branch of PAN in The Netherlands. She’s an MD and PhD researcher at Reade Rheumatology and Amsterdam University Medical Center. She investigates the influence of a plant-based lifestyle program on patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, especially the microbiome and implementation in healthcare.

Wendy Walrabenstein, RD is the Treasurer for the branch of PAN in The Netherlands. She’s a dietician and PhD researcher at Reade Rheumatology in Amsterdam and Amsterdam University Medical Center. She investigates the effect of a plant-based lifestyle program on people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Author of the book “Food Body Mind” which addresses the effects of lifestyle on inflammation and ageing, lecturer in Nutrition & Dietetics at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, but also an economist with 15 years of experience in the international financial world.

-

Ritchie H, Roser M. Forests and Deforestation. 2021. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation

Alexander, P., Brown, C., Arneth, A., Finnigan, J., & Rounsevell, M. D. (2016). Human appropriation of land for food: the role of diet. Global Environmental Change, 41, 88-98. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378016302370?via%3Dihub#bib0330

Dagevos H, Verhoog D, van Horne P, Hoste Robert. Vleesconsumptie per hoofd van de bevolking in Nederland 2005-2019 (Translation: Meat consuption per person in the Dutch population 2005-2019). September 2020. Available at: https://edepot.wur.nl/531409.

The Dutch Soy Coalition. Soy Barometer 2014. Available at: https://www.profundo.nl/download/sojacoalitie1410a

Messina M, Messina V. The role of soy in vegetarian diets. Nutrients. 2010;2(8):855-888.

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2021) – “Forests and Deforestation”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation’ [Online Resource]

Brandão, ASP, de Rezende, GC, Costa Marques, RW, & de Aplicada, IPE (2005). Agricultural growth in the period 1999-2004, explosion of the area planted with soybeans and the environment in Brazil.

Müller, C. (2003). Expansion and modernization of agriculture in the Cerrado–the case of soybeans in Brazil’s center-West. Brasília: Departamento de Economia, Universidade de Brasília.

Barona, E., Ramankutty, N., Hyman, G., & Coomes, O. T. (2010). The role of pasture and soybean in deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. Environmental Research Letters, 5(2), 024002.

Alpro. Frequently asked questions. Available at: https://www.alpro.com/sg/faq/

European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on genetically modified food and feed. 2003, September 22. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32003R1829

American Institute for Cancer Research. Soy: Intake Does Not Increase Risk for Breast Cancer Survivors. Available at: http://www.aicr.org/foods-that-fight-cancer/soy.html#research

Béliveau R, Gingras D. Eten tegen kanker: de rol van voeding bij het ontstaan van kanker (Translation: Eating against cancer: the role of food in the development of cancer). 6th edition. Utrecht/Antwerpen: Kosmos Publishers; 2011.

Moorehead RA. Rodent Models Assessing Mammary Tumor Prevention by Soy or Soy Isoflavones. Genes. 2019; 10(8):566. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10080566

Soukup, S.T., Helppi, J., Müller, D.R. et al. Phase II metabolism of the soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein in humans, rats and mice: a cross-species and sex comparison.Arch Toxicol 90, 1335–1347 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-016-1663-5

Setchell KD, Brown NM, Zhao X, Lindley SL, Heubi JE, King EC, Messina MJ. Soy isoflavone phase II metabolism differs between rodents and humans: implications for the effect on breast cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Nov;94(5):1284-94. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.019638. Epub 2011 Sep 28. PMID: 21955647; PMCID: PMC3192476.

Fan Y, Wang M, Li Z, Jiang H, Shi J, Shi X, Liu S, Zhao J, Kong L, Zhang W and Ma L (2022) Intake of Soy, Soy Isoflavones and Soy Protein and Risk of Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Front. Nutr. 9:847421. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.847421

World Cancer Research fund International. Global cancer data by country. 2022, March 23. Available at: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/global-cancer-data-by-country/

Pulitzer Center. Cancer’s Global Footprint. Breast Cancer Incidence. 2008. Available at: http://globalcancermap.com/

Chen M, Rao Y, Zheng Y, et al. Association between soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer risk for pre- and post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89288.

Nechuta SJ, Caan BJ, Chen WY, et al. Soy food intake after diagnosis of breast cancer and survival: an in-depth analysis of combined evidence from cohort studies of US and Chinese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):123-132.

Kroenke CH, Kwan ML, Sweeney C, et al. High- and Low-Fat Dairy Intake, Recurrence, and Mortality After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(9):616-623.

Lu W, Chen H, Niu Y, et al. Dairy products intake and cancer mortality risk: a meta-analysis of 11 population-based cohort studies. Nutrition Journal. 2016;doi: 10.1186/s12937-016-0210-9.

Diallo A, Deschasaux M, Latino-Martel P, Hercberg S, Galan P, Fassier P, Allès B, Guéraud F, Pierre FH, Touvier M. Red and processed meat intake and cancer risk: Results from the prospective NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2018 Jan 15;142(2):230-237. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31046. Epub 2017 Oct 16. PMID: 28913916.

Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;116:1970-1980.

Schlemmer U, Frølich W, Prieto RM, et al. Phytate in foods and significance for humans: Food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2009;53:S330-S375.

Messina M, Redmond G. Effects of soy protein and soybean isoflavones on thyroid function in healthy adults and hypothyroid patients: a review of the relevant literature. Thyroid. 2006;16:249-258.

Divi RL, Chang HC, Doerge DR. Anti-thyroid isoflavones from soybean: isolation, characterization, and mechanisms of action. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1087-1096.

Zorginstituut Nederland. Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas. Levothyroxine. Available at: https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren-volgens-boek/preparaatteksten/l/levothyroxine

Wu SH, Shu XO, Chow WH, et al. Soy food intake and circulating levels of inflammatory markers in Chinese Women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:996-1004.

Messina M. Soy and Health Update: Evaluation of the Clinical and Epidemiologic Literature. Nutrients. 2016 Nov 24;8(12):754. doi: 10.3390/nu8120754. PMID: 27886135; PMCID: PMC5188409.

Li N, Wu X, Zhuang W, Xia L, Chen Y, Zhao R, Yi M, Wan Q, Du L, Zhou Y. Soy and Isoflavone Consumption and Multiple Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomized Trials in Humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2020 Feb;64(4):e1900751. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900751. Epub 2019 Oct 14. PMID: 31584249.