Rheumatoid Arthritis and Diet: A Physician’s Guide

By Carlijn Wagenaar, MD and Wendy Walrabenstein, RD from PAN The Netherlands.

“Doctor, what should I eat to reduce my joint complaints?”

“What can I do to prevent my disease from progressing?”

Have you ever found yourself sitting across from a rheumatoid arthritis patient who is asking you for diet or lifestyle tips? Which recommendations, if any, did you give your patient? With this overview article we hope to inform you about the current evidence between lifestyle, and in particular diet, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We hope that you will be able to use this knowledge to give advice to your patients next time in order to empower them to make healthy lifestyle choices.

What is rheumatoid arthritis?

Arthritis is a general term used for disorders that affect the joints. While there are many types of arthritis, one of the most common types is rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic systemic autoimmune disease which causes pain and swelling of the joints and can ultimately result in joint damage and disability (1). RA affects about 0.24% of the world population, although it has been estimated that the prevalence in the United States and countries in northern Europe is even higher (between 0.5% and 1%)(1-3).

Due to tremendous advances in RA treatment, including the introduction of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), poor long-term outcomes have been reduced (4,5). Yet, long-term RA complications still include physical and work disability, reduced quality of life, joint replacement surgeries, development of other chronic diseases (including cardiovascular disease), and premature mortality (6). The financial impact of RA on society and the healthcare system, therefore, remains significant. The majority of this is due to drug costs as well as indirect costs from absenteeism and work disability (7).

What causes rheumatoid arthritis?

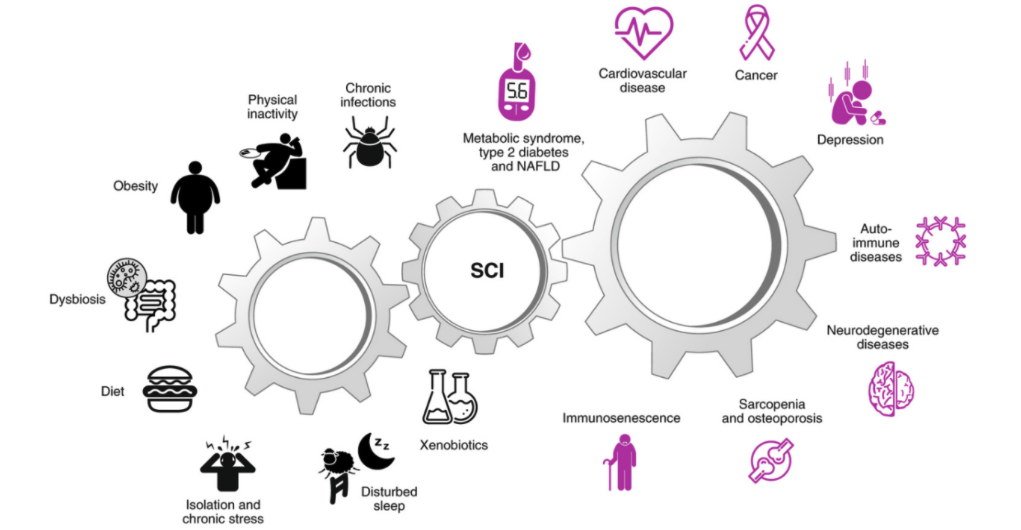

Around 16% of RA cases are caused, in part, by genetic factors – although this number may be even lower as certain genes may only be expressed in unfavourable environments (8,9). Additionally, a key characteristic of many chronic diseases is the presence of low-grade inflammation. Low-grade inflammation is commonly triggered by (lifestyle) factors such as physical inactivity, obesity, disbalance of the microbiome, poor diet, stress, impaired sleep, and exposure to, for example, air pollution or smoking (10). In turn, low-grade inflammation can cause or facilitate a break in immune tolerance, and thus play a role in the development of various autoimmune diseases (10). Also, low-grade inflammation increases with age and the combination of ageing and inflammation (also known as “Inflammageing”) seems to be associated with many chronic diseases, including RA (10).

Image: Causes and consequences of low-grade systemic chronic inflammation (10).

Which lifestyle factors are related to rheumatoid arthritis?

Furthermore, the risk of developing RA is related to various lifestyle factors including:

An unhealthy diet (11)

Obesity (12,13)

Smoking (14, 13)

Sedentary lifestyle (15)

Stress (16-18)

In this article, we will focus on how dietary choices can influence RA. Before we dive in to look at the various aspects of nutrition, let’s take a brief look at how each of the above lifestyle factors contributes to RA risk.

Diet: One study found long-term adherence to a higher-quality dietary pattern, using the AHEI-2010 score, was associated with reduced RA risk. Specifically, a lower intake of red meat was found to be one of the components most associated with decreased RA risk (11).

Obesity and smoking: Smoking and obesity also increase RA risk (12,13,14). One study found smoking increased the risk of developing RA by 10 times while overweight individuals (BMI≥25 kg/m²) had a 6-fold increased risk of developing RA compared to individuals at a normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m²) (13).

Sedentary lifestyle: Furthermore, physical activity has been found to be a protective factor for RA. One study grouped women based on physical activity levels and found those in the highest category (40 – 60 minutes per day walking/biking and 2 – 3 hours per week of exercise) had a 35% lower risk of RA compared to the lowest category (<20 minute per day of walking/bicycling and <1 hour per week of exercise) (15).

Stress: The onset of RA has also been linked to stress (16,18,19). Specifically, people with post-traumatic stress disorder have been found to have a 76 – 100% increased risk of developing autoimmune disorders including RA (18,19).

Aside from dietary choices (which we’ll get into later), lifestyle recommendations for all patients with RA include the following:

maintaining a healthy body weight

undertaking sufficient exercise (150 – 300 minutes of moderate aerobic physical activity throughout the week and muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week)

limiting the amount of time spent being sedentary

quitting smoking

reducing stress (37, 72)

The links between the microbiome and autoimmunity

The microbiome consists of communities of microorganisms living on and in our bodies and has various functions including communicating with the immune system to support its development and regulate inflammatory responses (20,21).

Numerous studies have found a link between the microbiome and autoimmunity. The scientific consensus is clear that the gut microbiome plays a role in triggering and driving systemic autoimmunity, although there is still discussion about the specific means by which this takes place (22). The composition and ratio of bacterial species within this community can differ considerably based on many factors – in particular health status – whereby a greater diversity of microorganisms is associated with better health (23,24).

Furthermore, gut microbiome dysbiosis (defined as an imbalance in the amount and function of the gut microbial community) is associated with chronic inflammatory diseases including autoimmune diseases (24,25).

Additionally, the gut microbiome of RA patients contains proportionately more of certain types of bacteria such as Prevotella copri (especially in recently diagnosed patients) and Lactobacillus salivarius (26). It has been suggested that Prevotella copri may cross the gut wall and play a role in the development of RA (27).

Growing evidence suggests that microbiome dysbiosis can also lead to increased intestinal permeability (‘leaky gut’) and ultimately fuel host immune responses and chronic inflammatory disorders (20,28). Specifically for RA, an association between the mouth microbiome and gum disease has been found, whereby specific bacteria can stimulate the production of inflammatory compounds that may trigger antibodies related to RA (29).

Diet and rheumatoid arthritis

As mentioned earlier, treatment options for RA patients have improved significantly, yet less than half of patients attain long-term disease remission and many experience drug side effects (30,31). There is, however, great potential for lifestyle interventions to help prevent and treat RA, although the impact of these interventions is often unknown and thus they are under-used.

General recommendations

For patients with RA and other inflammatory rheumatic diseases, general guidelines for a healthy diet (such as from the WHO or national guidelines) are a good starting point (32, 72). These recommendations aim to reduce risk factors related to cardiovascular disease, for which RA patients have up to 2 times higher risk than the general population (33).

The following are recommendations for all, including RA patients, for a healthy diet (32):

Eat a variety of fruit, vegetables, legumes (e.g., lentils, beans), nuts, and whole grains (e.g., whole wheat flour, whole grain pasta, brown rice).

Aim for at least 400 g of fruits and vegetables (around 5 servings) per day.

Limit added sugar to less than 12 teaspoons sugar per day (although less than 6 teaspoons is even better) (e.g., sweets, soda, fruit juices, syrups).

Aim for less than 5 g of salt intake per day. Excessive salt intake has been found to be associated with a higher risk of developing RA (34).

Aim for less than 66 grams of fat intake per day. Limit saturated fat intake to under 22 grams per day. Saturated fats are found primarily in animal-based products such as meat, dairy, and eggs.

Saturated fatty acids and omega-6 fatty acids are associated with increased inflammation. Instead, use oils such as flaxseed that are rich in omega-3 fatty acids instead or oils such as olive oil that are rich in omega-9 fatty acids (35,36).

Interactions between medication and alcohol are important to consider for RA patients. For those taking NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or other medications that are metabolized in the liver or associated with an increased risk of abnormal liver values, alcohol consumption is not recommended.

The use of nutrient supplements is not necessary, except for people who belong to a specific group for which supplementation is recommended (for more information see the supplements section below).

The important role of dietary fibre

Fibre is a key component of a healthy diet. High fibre intake appears to improve health in people with rheumatic diseases, as it is associated with the following:

significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease

lower blood pressure and serum cholesterol

improved glucose levels and insulin sensitivity

facilitates weight loss

seems to improve immune function (38)

Increased fibre intake has also been shown to increase anti-inflammatory immune cells and decrease markers for bone erosion in patients with RA (39).

Daily fibre intake also plays a vital role in the microbiome changes associated with diet (25,40). In the gut, non-digestible carbohydrates are fermented by the microbiome to form short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have anti-inflammatory qualities. Besides, some types of dietary fibre can selectively stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria in the colon and thus promote health (40-43).

High-fibre diets (e.g., vegetarian, Mediterranean, vegan), that are low in red meat and high in unsaturated fatty acids, are associated with more beneficial microbiome composition, increased microbial diversity, and more health-promoting bacteria as well as higher levels of SCFAs (42, 44-46). In contrast, typical Western diets characterized by high animal fat and protein and low fibre consumption, show an overall decrease in total bacteria and certain beneficial bacterial species, while at the same time increasing certain pathogenic bacteria (42).

Plant-based dietary interventions, such as vegetarian and vegan diets, were found to be consistently more effective at improving clinical and microbiome outcomes than other dietary interventions, including Mediterranean dietary patterns, in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases including RA (47).

Especially for those who get abdominal complaints when eating fibre-rich foods (such as beans), it may be recommended to slowly build up fibre intake, eat a diversity of plant foods, and incorporate fermented foods into the diet (e.g., kimchi, kombucha, sauerkraut, (soy) yoghurt). Fermented foods have been found to increase microbiome diversity and reduce inflammation whilst being gentle on the gut (48).

Whole food plant-based diets and the Mediterranean diet in rheumatoid arthritis

Various studies have shown the potential benefits of plant-based or Mediterranean diets in patients with RA. A vegetarian diet was found to be effective after one year in a Norwegian, single-blind, randomized controlled trial with 53 RA patients (49). In this study, the intervention group underwent a 7 – 10 day fast in a clinic, after which they followed a plant-based, gluten-free diet for 3.5 months. After this period, the patients were allowed to re-introduce gluten and dairy for the remaining 9 months. Inflammation, pain, morning stiffness, general well-being, grip strength, and tender and painful joint counts were measured regularly. All of the above improved significantly at all time points compared to baseline and the control group, who followed a standard (omnivore) diet (49).

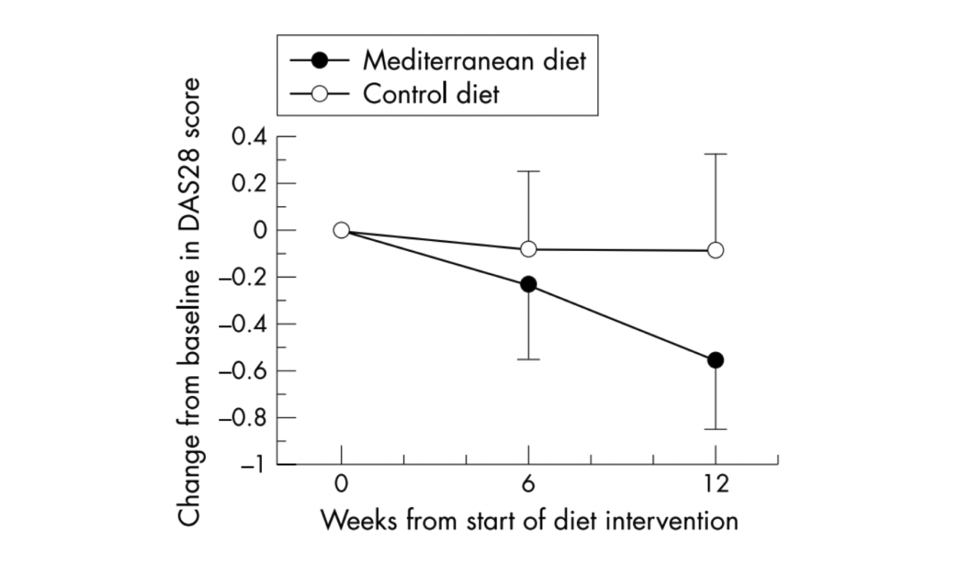

Additionally, in a Swedish randomized controlled trial with 51 RA patients, the effect of a Mediterranean diet was investigated on disease activity (using the DAS28 score – a composite score used to measure disease activity in RA). Figure 1 shows the intervention significantly reduced disease activity within 12 weeks (50).

Image: Disease activity (DAS28 score) at baseline and at weeks 6 and 12. The results are presented in relative terms, where the baseline value is set to zero, as mean values with 95% confidence intervals. (50)

A more recent Swedish cross-over study compared a similar diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids (from fatty fish and nuts), fibre, antioxidants, and probiotics to a typical Swedish diet consisting of higher amounts of animal protein, fat and refined grains. After 10 weeks, there was no significant difference found in the DAS28 score between the intervention and control group, although within the intervention group the DAS28 did improve significantly compared to the start of the intervention (51).

Moreover, a recent study from the United States investigated whether a plant-based diet with no energy restriction, but with the elimination of specific foods (e.g., gluten-containing foods, table sugar) followed by their reintroduction, affected disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to a placebo group. In this 16-week cross-over study (both the diet and placebo phase were 16 weeks long with a 4-week wash-out period), the DAS28 score and number of swollen joints decreased significantly in the diet phase compared to the control group (52).

Gluten-free diets and rheumatoid arthritis

Some studies have investigated the effects of gluten-free variants of the whole-food plant-based diet (WFPD) in RA (53,54). It is still unclear to what extent the gluten-free component of the diet further contributes to a positive effect on inflammation or other symptoms (e.g., fatigue). However, in practice, some RA patients already on a WFPB diet experience further improvements after also switching to gluten-free. It may be worthwhile to experiment with gluten-free foods in addition to a WFPB or a Mediterranean diet for a short period, such as a couple of months, to determine if it improves symptoms even more. Yet, as eating enough fibre on a gluten-free diet can be more difficult, it is recommended to only cut out gluten-containing foods when there is a clinical benefit.

The impact of fasting on rheumatoid arthritis

Several studies show a short period of fasting followed by a vegetarian diet can cause clinically relevant long-term improvement in patients with RA (49, 54-57, 73). Although methods vary, they generally involve fasting periods of 7 – 10 days with a daily intake of 0-800 kcal. Although more scientific evidence is needed, fasts lasting 3 – 4 days may also be sufficient, and water fasting (<100 kcal per day) may be less effective than fasting based on vegetable soups and juices containing up to 800 kcal per day. The most well-known fasting method is the Buchinger method, in which, after a ‘tapering day,’ patients consume vegetable juices and broth (an average intake of 500 kcal per day). The Buchinger method is offered in clinics in Germany, where it is combined with other therapies such as relaxation exercises and gentle movement (e.g., yoga).

Malnutrition and muscle loss

A point of concern for RA patients is malnutrition, due to nutrient deficiencies, and loss of muscle mass. For RA patients adequate nutrient intake may be more difficult due to, for example, reduced appetite and nausea as a side effect of medication (especially with the common use of methotrexate). Also, corticosteroid use and chronic inflammation both play a role in muscle wasting and thus reduced muscle mass (74, 75).

Sarcopenia is a decrease in muscle mass, strength, and function, that is associated with increased mortality and morbidity, and its prevalence is increased in patients with RA (up to 45%) (58). Consequently, extra attention should be paid to ensure sufficient protein and energy intake in RA patients at risk of or with malnutrition and/or sarcopenia.

Supplements and rheumatoid arthritis

Depending on the individual’s diet, medication use, and some other factors, supplementation may be recommended for some patients with RA. Whole foods should be the first source of nutrients and should be preferred over so-called nutritional supplements. Yet, in some cases nutritional supplements can be advised or of added benefit. Nutritional supplements should be used only after having consulted a physician and/or dietitian who are familiar with the respective guidelines regarding supplement prescriptions. It is important to make sure that an individual receives recommendations according to individual needs and health conditions from trained healthcare professionals.

Please note that the following are general recommendations only. Please refer to local guidelines for specific advice on individual supplement recommendations.

Folic acid: Patients with rheumatic diseases who are prescribed methotrexate (MTX is a drug that is taken weekly, orally or subcutaneously), should also receive a prescription for folic acid, as MTX is a folic acid antagonist. Patients are usually instructed to take at least 5 g of folic acid at least 24 hours after taking MTX to reduce the risk of hepatoxicity (59).

Vitamin D: Depending on age, skin pigmentation, and daily sunlight exposure, many patients with RA may be instructed to take 10 to 20 μg of vitamin D per day. A cohort study found that women with the highest total vitamin D intake had a 33% lower risk of RA compared to women in the lowest group (60). Also, for those following a completely plant-based diet, dietary intake of vitamin D may be low, so it is recommended to supplement with 25 – 50 μg (1,000 – 2,000 IU) per day (61).

Vitamin B12: In general, those eating primarily plant-based foods, including those with RA, should take a supplement for vitamin B12, as plant-based foods either do not contain vitamin B12 at all or in negligible amounts. Some plant-based products (e.g., dairy alternatives) are fortified with vitamin B12, although this is usually not the case for organic products. In general, the intake of vitamin B12 from fortified foods may be too low and can vary a lot depending on the product and the country. Therefore, a supplement is generally recommended to ensure adequate intake.

Only some of the vitamin B12 ingested is absorbed, so supplementation dosage is always higher than the recommended daily amount (e.g., 250 – 500 mcg cyanocobalamin or 1,000 mcg methylcobalamin).

Calcium: Corticosteroids are regularly used in RA patients and increase the risk of osteoporosis. With prolonged use of more than 3 months of higher doses of corticosteroids (more than 7.5 mg), supplementation of calcium is often recommended in order to counteract the increased risk for osteoporosis.

Omega 3 fatty acids: A meta-analysis of ten studies found that supplementing at least 2.7 g of omega-3 fatty acids per day for three months significantly reduced the use of NSAIDs in patients with RA (62). A trend towards a decrease in disease activity was also found, although it was not significant.

Examples of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids are fatty fish, flaxseed, chia seed, walnuts, and algae. People who wish to supplement omega-3 fatty acids and follow a plant-based diet can use algae oil supplements. Although fish and fish oil are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, they contain relatively more heavy metals and toxins than other omega-3-rich sources like algae. On average, fish only makes up 1-2% of the diet, but it has been found to contribute more than 50% of the total intake of dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs and heavy metals in adults (63). When consumed daily at the recommended dosage, fish oil supplementation can contribute to exceeding the tolerable daily intake of certain heavy metals and toxins (64).

Curcumin: Curcumin is the main curcuminoid (polyphenolic pigment) found in turmeric and has anti-inflammatory properties. Curcumin makes up 77% of the curcuminoids found in turmeric, whereby only 2.5-6% of turmeric is made up of curcuminoids (76). To date, a good amount of research has been done on the effectiveness of curcumin supplementation. A 2019 systematic review found inconclusive results for the effects of curcumin in RA, although many studies were rejected because they were performed without a control group (65). Important to also note is that, within the field, various studies have been funded by companies that produce their own supplements.

In RA, an eight-week controlled clinical study showed that daily supplementation with 1000 mg curcuminoids was as effective as a combination of 1000 mg curcuminoids with 100 mg diclofenac or only 100 mg diclofenac (66). The authors state the molecular mechanisms of curcumin are unclear, but they speculate curcumin may regulate molecular targets that control chronic pain (66). Also, an animal study showed that curcumin supplementation may benefit rats with arthritis treated with methotrexate. In this study, the addition of curcumin appeared to be beneficial for both arthritis and reducing hepatotoxicity (67).

Curcumin supplementation appears to be safe up to a maximum of 12 g per day (68). It is important to consider the blood pressure-lowering effect of curcumin in those who use blood pressure-lowering medication. To improve the bioavailability of curcumin it is recommended to combine it with black pepper to enhance its health benefits (69).

Conclusions and recommendations for specific diets and nutrients in rheumatoid arthritis

Despite the positive outcomes regarding dietary patterns consisting mainly of plant foods, more studies are needed to reproduce these findings (53). Nevertheless, a (predominantly) whole food plant-based or Mediterranean diet can be recommended for patients with RA, in addition to the general healthy diet recommendations and nutrient intake discussed in this article.

Fortunately, more research is currently being conducted in this field including the Plants for Joints study in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where the effect of a multidisciplinary lifestyle program including a plant-based diet, movement, and stress and sleep management is being investigated for patients with (increased risk of) RA (70). Additionally in Berlin, Germany, another randomized controlled trial is investigating the effects of either fasting followed by a plant-based diet or an anti-inflammatory diet in patients with RA (71). So, we expect new and exciting research findings in that area in the next few years!

Additional Information:

-

Carlijn Wagenaar, MD is the Chairperson for the branch of PAN in The Netherlands. She’s an MD and PhD researcher at Reade Rheumatology and Amsterdam University Medical Center. She investigates the influence of a plant-based lifestyle program on patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, especially the microbiome and implementation in healthcare.

Wendy Walrabenstein, RD is the Treasurer for the branch of PAN in The Netherlands. She’s a dietician and PhD researcher at Reade Rheumatology in Amsterdam and Amsterdam University Medical Center. She investigates the effect of a plant-based lifestyle program on people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Author of the book “Food Body Mind” which addresses the effects of lifestyle on inflammation and ageing, lecturer in Nutrition & Dietetics at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, but also an economist with 15 years of experience in the international financial world.

-

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Carmona L, Wolfe F, Vos T, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(7):1316-1322.

Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum 2010 Jun;62(6):1576-1582.

Hunter TM, Boytsov NN, Zhang X, Schroeder K, Michaud K, Araujo AB. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004-2014. Rheumatol Int 2017 Sep;37(9):1551-1557.

Krishnan E, Lingala B, Bruce B, Fries JF. Disability in rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biological treatments. Ann Rheum Dis 2012 Feb;71(2):213-218.

Aga AB, Lie E, Uhlig T, Olsen IC, Wierød A, Kalstad S, et al. Time trends in disease activity, response and remission rates in rheumatoid arthritis during the past decade: results from the NOR-DMARD study 2000-2010. Ann Rheum Dis 2015 Feb;74(2):381-388.

England B, Mikuls T. Epidemiology of, risk factors for, and possible causes of rheumatoid arthritis. 2022; Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-of-risk-factors-for-and-possible-causes-of-rheumatoid-arthritis.

Hsieh PH, Wu O, Geue C, McIntosh E, McInnes IB, Siebert S. Economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of literature in biologic era. Ann Rheum Dis 2020 Jun;79(6):771-777.

Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science 2002 Apr 26;296(5568):695-698.

Viatte S, Plant D, Raychaudhuri S. Genetics and epigenetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013 Mar;9(3):141-153.

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med 2019 Dec;25(12):1822-1832.

Hu Y, Sparks JA, Malspeis S, Costenbader KH, Hu FB, Karlson EW, et al. Long-term dietary quality and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis in women. Ann Rheum Dis 2017 Aug;76(8):1357-1364.

Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Davis JM,3rd, Gabriel SE. Contribution of obesity to the rise in incidence of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013 Jan;65(1):71-77.

de Hair MJ, Landewé RB, van de Sande, M. G., van Schaardenburg D, van Baarsen LG, Gerlag DM, et al. Smoking and overweight determine the likelihood of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013 Oct;72(10):1654-1658.

Di Giuseppe D, Discacciati A, Orsini N, Wolk A. Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014 Mar 5;16(2):R61.

Di Giuseppe D, Bottai M, Askling J, Wolk A. Physical activity and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women: a population-based prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2015 Mar 4;17(1):40-2.

van Middendorp H, Evers AW. The role of psychological factors in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: From burden to tailored treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016 Oct;30(5):932-945.

Lee YC, Agnew-Blais J, Malspeis S, Keyes K, Costenbader K, Kubzansky LD, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Risk for Incident Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 Mar;68(3):292-298.

O’Donovan A, Cohen BE, Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Margaretten M, Nishimi K, et al. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2015 Feb 15;77(4):365-374.

Lee YC, Agnew-Blais J, Malspeis S, Keyes K, Costenbader K, Kubzansky LD, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Risk for Incident Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 Mar;68(3):292-298.

Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res 2020 Jun;30(6):492-506.

Blander JM, Longman RS, Iliev ID, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat Immunol 2017 Jul 19;18(8):851-860.

Manasson J, Blank RB, Scher JU. The microbiome in rheumatology: Where are we and where should we go? Ann Rheum Dis 2020 Jun;79(6):727-733.

Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, Spector TD. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018 Jun 13;361:k2179.

Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, et al. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019 Jan 10;7(1):14. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7010014.

Illiano P, Brambilla R, Parolini C. The mutual interplay of gut microbiota, diet and human disease. FEBS J 2020 Mar;287(5):833-855.

Jethwa H, Abraham S. The evidence for microbiome manipulation in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017 Sep 1;56(9):1452-1460.

Pianta A, Arvikar SL, Strle K, Drouin EE, Wang Q, Costello CE, et al. Two rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantigens correlate microbial immunity with autoimmune responses in joints. J Clin Invest 2017 Aug 1;127(8):2946-2956.

Allam-Ndoul B, Castonguay-Paradis S, Veilleux A. Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Trans-Epithelial Permeability. Int J Mol Sci 2020 Sep 3;21(17):6402. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176402.

Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife 2013 Nov 5;2:e01202.

Ajeganova S, Huizinga T. Sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: latest evidence and clinical considerations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2017 Oct;9(10):249-262.

Grove ML, Hassell AB, Hay EM, Shadforth MF. Adverse reactions to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in clinical practice. QJM 2001 Jun;94(6):309-319.

World healthy organization. Healthy diet. 2020; Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

Hansildaar R, Vedder D, Baniaamam M, Tausche AK, Gerritsen M, Nurmohamed MT. Cardiovascular risk in inflammatory arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and gout. Lancet Rheumatol 2021 Jan;3(1):e58-e70.

Sigaux J, Semerano L, Favre G, Bessis N, Boissier MC. Salt, inflammatory joint disease, and autoimmunity. Joint Bone Spine 2018 Jul;85(4):411-416.

Calder PC. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Inflammation, and Inflammatory Diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2006 Jun;83(6 Suppl):1505S-1519S.

Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: from molecules to man. Biochem Soc Trans 2017 Oct 15;45(5):1105-1115.

World Health Organisation. Physical activity. 2020; Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH,Jr, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev 2009 Apr;67(4):188-205.

Häger J, Bang H, Hagen M, Frech M, Träger P, Sokolova MV, et al. The Role of Dietary Fiber in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Feasibility Study. Nutrients 2019 Oct 7;11(10):2392. doi: 10.3390/nu11102392.

Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients 2013 Apr 22;5(4):1417-1435.

Mukherjee A, Lordan C, Ross RP, Cotter PD. Gut microbes from the phylogenetically diverse genus Eubacterium and their various contributions to gut health. Gut Microbes 2020 Nov 9;12(1):1802866.

Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med 2017 Apr 8;15(1):73-y.

Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017 Mar 4;8(2):172-184.

Tomova A, Bukovsky I, Rembert E, Yonas W, Alwarith J, Barnard ND, et al. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front Nutr 2019 Apr 17;6:47.

De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010 Aug 17;107(33):14691-14696.

De Filippis F, Pellegrini N, Vannini L, Jeffery IB, La Storia A, Laghi L, et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016 Nov;65(11):1812-1821.

Wagenaar CA, van de Put M, Bisschops M, Walrabenstein W, de Jonge CS, Herrema H, et al. The Effect of Dietary Interventions on Chronic Inflammatory Diseases in Relation to the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021 Sep 15;13(9):3208. doi: 10.3390/nu13093208.

Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, Dahan D, Merrill BD, Yu FB, et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 2021 Aug 5;184(16):4137-4153.e14.

Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Haugen M, Borchgrevink CF, Laerum E, Eek M, Mowinkel P, et al. Controlled trial of fasting and one-year vegetarian diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1991 Oct 12;338(8772):899-902.

Sköldstam L, Hagfors L, Johansson G. An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003 Mar;62(3):208-214.

Vadell AKE, Bärebring L, Hulander E, Gjertsson I, Lindqvist HM, Winkvist A. Anti-inflammatory Diet In Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADIRA)-a randomized, controlled crossover trial indicating effects on disease activity. Am J Clin Nutr 2020 Jun 1;111(6):1203-1213.

Barnard ND, Levin S, Crosby L, Flores R, Holubkov R, Kahleova H. A Randomized, Crossover Trial of a Nutritional Intervention for Rheumatoid Arthritis. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2022:15598276221081819.

Hagen KB, Byfuglien MG, Falzon L, Olsen SU, Smedslund G. Dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD006400. doi(1):CD006400.

Hafström I, Ringertz B, Gyllenhammar H, Palmblad J, Harms-Ringdahl M. Effects of fasting on disease activity, neutrophil function, fatty acid composition, and leukotriene biosynthesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988 May;31(5):585-592.

Sköldstam L, Larsson L, Lindström FD. Effect of fasting and lactovegetarian diet on rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1979;8(4):249-255.

Abendroth A, Michalsen A, Lüdtke R, Rüffer A, Musial F, Dobos GJ, et al. Changes of Intestinal Microflora in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis during Fasting or a Mediterranean Diet. Forsch Komplementmed 2010;17(6):307-313.

Udén AM, Trang L, Venizelos N, Palmblad J. Neutrophil functions and clinical performance after total fasting in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1983 Feb;42(1):45-51.

An HJ, Tizaoui K, Terrazzino S, Cargnin S, Lee KH, Nam SW, et al. Sarcopenia in Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci 2020 Aug 7;21(16):5678. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165678.

Liu L, Liu S, Wang C, Guan W, Zhang Y, Hu W, et al. Folate Supplementation for Methotrexate Therapy in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Rheumatol 2019 Aug;25(5):197-202.

Merlino LA, Curtis J, Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Criswell LA, Saag KG, et al. Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Arthritis Rheum 2004 Jan;50(1):72-77.

Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016 Dec;116(12):1970-1980.

Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res 2012 Jul;43(5):356-362.

Bilau M, Matthys C, Baeyens W, Bruckers L, De Backer G, Den Hond E, et al. Dietary exposure to dioxin-like compounds in three age groups: results from the Flemish environment and health study. Chemosphere 2008 Jan;70(4):584-592.

Bourdon JA, Bazinet TM, Arnason TT, Kimpe LE, Blais JM, White PA. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) contamination and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist activity of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements: implications for daily intake of dioxins and PCBs. Food Chem Toxicol 2010 Nov;48(11):3093-3097.

Yang M, Akbar U, Mohan C. Curcumin in Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases. Nutrients 2019 May 2;11(5):1004. doi: 10.3390/nu11051004.

Chandran B, Goel A. A randomized, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Phytother Res 2012 Nov;26(11):1719-1725.

Banji D, Pinnapureddy J, Banji OJ, Saidulu A, Hayath MS. Synergistic activity of curcumin with methotrexate in ameliorating Freund’s Complete Adjuvant induced arthritis with reduced hepatotoxicity in experimental animals. Eur J Pharmacol 2011 Oct 1;668(1-2):293-298.

Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm 2007;4(6):807-818.

Mimica B, Bučević Popović V, Banjari I, Jeličić Kadić A, Puljak L. Methods Used for Enhancing the Bioavailability of Oral Curcumin in Randomized Controlled Trials: A Meta-Research Study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022 Jul 28;15(8):939. doi: 10.3390/ph15080939.

Walrabenstein W, van der Leeden M, Weijs P, van Middendorp H, Wagenaar C, van Dongen JM, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary lifestyle program for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, an increased risk for rheumatoid arthritis or with metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis: the “Plants for Joints” randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials 2021;22(1):715.

Hartmann AM, Dell’Oro M, Kessler CS, Schumann D, Steckhan N, Jeitler M, et al. Efficacy of therapeutic fasting and plant-based diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (NutriFast): study protocol for a randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 2021 Aug 11;11(8):e047758-047758.

Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Balanescu A, et al2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Published Online First: 08 March 2022. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222020

Müller H, de Toledo FW, Resch KL. Fasting followed by vegetarian diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(1):1-10. doi: 10.1080/030097401750065256. PMID: 11252685.

Hasselgren PO, Alamdari N, Aversa Z, Gonnella P, Smith IJ, Tizio S. Corticosteroids and muscle wasting: role of transcription factors, nuclear cofactors, and hyperacetylation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010 Jul;13(4):423-8. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833a5107. PMID: 20473154; PMCID: PMC2911625.

Dalle S, Rossmeislova L, Koppo K. The Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 2017 Dec 12;8:1045. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01045. PMID: 29311975; PMCID: PMC5733049.

Lee WH, Loo CY, Bebawy M, Luk F, Mason RS, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin and its derivatives: their application in neuropharmacology and neuroscience in the 21st century. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013 Jul;11(4):338-78. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311040002. PMID: 24381528; PMCID: PMC3744901.