Get the Facts: An Introduction to Evidence-Based Nutrition

By Dr. Miriam Sonntag from the PAN Academy – our online learning platform where you can learn all about nutrition science.

Nutrition is more than fuel for the body. It is key to preventing or even reversing many of the leading chronic diseases that kill 41 million people each year (1). But with so much conflicting information, it is hard to know what to eat. This blog post helps you to sort facts from fiction. You will learn how to use evidence-based practice to transform your eating habits and improve your health.

What’s evidence-based practice?

Image: Dementia – An umbrella term for symptoms affecting cognitive functions and daily activities. Dementia stems from various brain-damaging causes that often coexist.

Evidence-based practice cuts through the noise and helps you make informed decisions about what to eat. How? By using the most reliable and up-to-date information available to guide your decisions (2). It involves finding and appraising all relevant high-quality scientific studies.

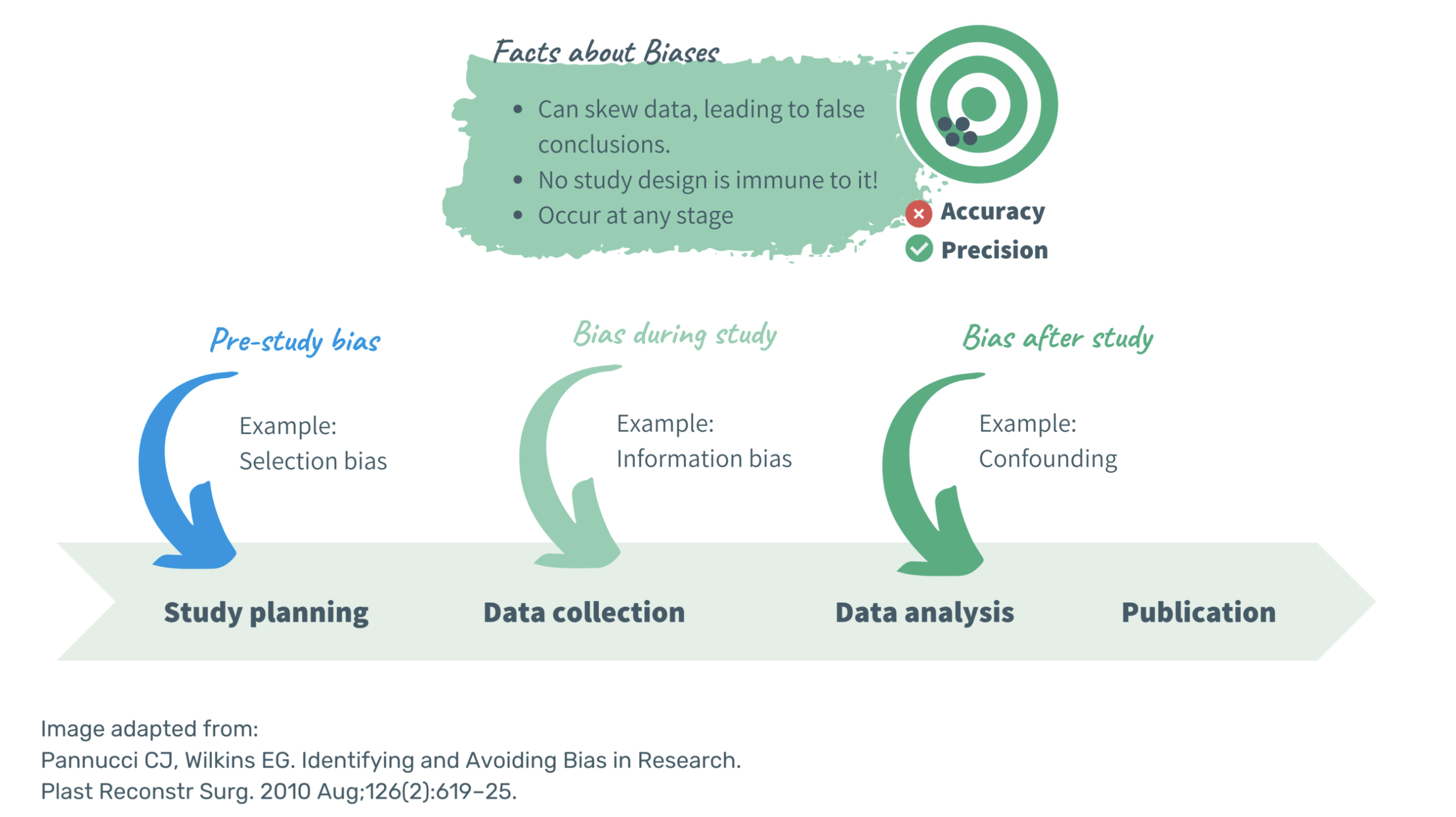

But what are these studies, and how do we judge their reliability? It is important to note that not all studies are created equal. Instead, there is a hierarchy of evidence. Study designs are ranked based on their likelihood of bias. The higher the risk of bias, the lower the level of evidence.

Bias is a systematic error causing distorted results and wrong conclusions. It affects all study designs and can occur at any stage of the research process (3). Bias impacts the validity and reliability of research findings. Yet, it is not the only downgrading factor. Limitations in the study design, inconsistent results or imprecise estimates can reduce the quality of observational studies and randomized controlled trials (4).

The Hierarchy of Evidence

The hierarchy of evidence is an important component of evidence-based medicine. Yet, its underlying quality criteria cannot be directly transferred to evidence-based nutrition. Let’s take a look at all relevant study designs included in the evidence-pyramid to find out why this is the case:

1. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses:

Meta-analyses, preferably of randomised controlled trials, represent the highest level of evidence. They provide a comprehensive overview of all relevant studies on a specific topic. These reviews combine and evaluate findings from similar studies to establish an overall effect size.

They can often provide more accurate and reliable results than a single study. Yet, we must keep in mind that they are only as good as the studies they include and how well the study designs match. It echoes the rubbish in, rubbish out concept. The validity of a meta-analysis depends on the quality of the studies used to support it. The greater the quantity and breadth of included studies, the less meaning the review holds. Whereas, the more studies that are excluded, the more subjective the analysis becomes.

Additionally, these reviews may not reflect the most current scientific knowledge. It can take years or even decades to incorporate the latest randomised controlled trials. Updating a meta-analysis requires synthesising a large amount of data from multiple studies. Yet, including too many studies can dilute results and impede conclusive findings.

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs):

RCTs are considered the gold standard of science. Subjects are randomly assigned to different groups. One group receives the new treatment (intervention group) while the other one receives a placebo or standard treatment (control group). Randomisation evens out known and unknown confounding factors that may affect the outcome.

Any differences in outcome can be attributed to the intervention being studied, rather than to other factors. Therefore, RCTs can prove causation. But the tightly controlled study design has its limitations. RCTs are by nature expensive and relatively short.

For drug trials, the short duration is not an issue. Drugs are designed to work quickly. But nutrients and the foods we eat are a different story. It can take years to see the benefits of a healthy diet in preventing chronic diseases. Unlike drugs, nutrients and foods have a wide range of effects and their impact may not be as noticeable (5). RCTs can provide one specific answer to one specific question. Yet, they might not be the best tool for studying the complex interaction between diet, lifestyle, and health (6). For example, RCTs are impractical when testing which diet is best for longevity.

A huge number of subjects would need to adhere to a specific diet for the rest of their lives to show significant differences. Yet, compliance is hard to control. People might change their eating habits or drop out of the study altogether. Thus, it is challenging to isolate the effects of a dietary intervention and answer what caused the measured effects. Are they attributable to what was eaten or what was replaced?

Observational Studies:

Observational studies, also known as epidemiological studies, are less reliable than RCTs and systematic reviews. But their findings, often called correlations, can still be meaningful. They can provide valuable insights into real-life situations.

No intervention is carried out. Instead, people’s lives are followed over a period of time. These studies help explore the associations between diet and health outcomes. They can identify the incidence, distribution and natural history of a disease within a population.

Although observational studies cannot establish causality, they can still be illuminating. They can help identify consistent patterns on a large scale. Especially when RCTs cannot be performed, these patterns should not be overlooked.

To make informed dietary choices, we need to look beyond individual studies. One topic can be studied in many ways. Each study provides just one perspective on the question at hand. Therefore, it is natural that the results will not always be the same.

The weight of evidence on a particular topic is key, though, and should drive health recommendations. We need to look at all the available data and piece it together. Where is the evidence as a whole pointing to?

Research is like a balancing act on an old-fashioned scale. The more weight on one side, the stronger the recommendation. Once the scale tips, the more evidence it requires to change course.

The likelihood of tipping towards one side not only depends on the total number of studies. It is way more important how a study was conducted and how reliable its findings are. Large, well-designed studies provide more robust results than smaller, poorly-designed ones.

To inform practical dietary advice, it is best to combine different lines of evidence. Real-world data from well-designed observational studies with findings from RCTs. Mechanistic studies in cells or animals may be fascinating, but their results do not always translate to humans.

How to implement the evidence-based process into practice?

Are you curious to know what the science truly says about how we should eat for optimal health? Seek strong evidence coming from studies involving human subjects. Avoid drawing conclusions from anecdotes, case studies or expert opinions. They are reflective reports rather than scientific evidence.

The next time you investigate a particular topic, start with one specific question and get the evidence:

Consider the overall body of evidence, not just a single study.

Weigh the pros and cons of each individual study

Put each study into context; how does it fit with our current understanding?

Don’t wait for flawless evidence or perfect understanding.

Seek robust and consistent patterns that emerge from different trial designs.

Always remain a bit sceptical; no single food item can perform miracles.

Additional Information:

-

Dr Miriam Sonntag is the Medical Content Executive of the online learning platform, PAN Academy. Having worked in basic research, she knows how to decipher complex information. Working now at PAN, she scans and pours over scientific papers and books. She breaks down the latest nutritional research into actionable advice for everyday life. She is committed to sharing the bigger picture of why it is good to put more plants on your plate.

-

Still confused about which study types provide robust and reliable results? This TED-Ed video by David H. Schwartz might help.

-

Non communicable diseases [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13;312(7023):71–2.

Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG. Identifying and Avoiding Bias in Research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 Aug;126(2):619–25.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, et al. What is ‘quality of evidence’ and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008 May 3;336(7651):995–8.

Blumberg J, Heaney RP, Huncharek M, Scholl T, Stampfer M, Vieth R, et al. Evidence-based criteria in the nutritional context. Nutr Rev. 2010 Aug;68(8):478–84.

Katz DL, Dansinger ML, Willett WC. The Study of Dietary Patterns: Righting the Remedies. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2021 Jul;35(6):875–8.